Ophelia George Mather was born on 1st September 1883 in Derby, Derbyshire, UK. Her parents were George Henry Mather, a draper and tailor, and his wife, Amelia Sarah Mather, nee George.

Ophelia trained to become a schoolteacher and lived in Derby all her life. She frequently had poems published in local newspapers and the following poem was also included in “One hundred of the Best Poems on the European War By Women Poets of the Empire” Edited by Charles Frederick Forshaw (Elliot Stock, London, 1916) pages 103 – 107.

“THE GLORY OF WAR” by Ophelia George Mather. Also published in “The Derby Daily Telegraph” on 8th October 1915

THERE'S glory in the khaki stream That passes through the station-gate! Perhaps there's glory in the gleam

That fills the eyes of those who wait ! Its glamour leads them to their homes, And blinds the bright eye w-hen it roams

Around the empty room ! Yet when away with day it steals, What suffering form is this, that kneels Half-fainting with the pain she feels At Glory's stroke of doom ?

Does Glory fill the heart of her

Who hears one voice in ev'ry sound,

And sees but one face everywhere^ And gazes hopelessly around,

Biting the lip to keep back tears

That bode to drown all future years In seas of misery?

Who tries to give, wath scarce a groan,

The only heart that matched her own,

Knowing that she is left alone With Glory's legacy?

Britain, with other lands, will boast How native warriors rushed to meet

The bold invaders of our coast

Until their downfall was complete !

How Glory stood where ranks were thin,

And cheered above the shrapnel-din, And smiled among the stench

Of reeking bodies, graveless still,

By silent wood and lonely hill,

Or sang its most triumphant trill,

In the death-haunted trench !

They'll tell how Glory stood its ground,

Where men half -gasped their lives away, And in the foulest vapours found

The incense of a hero's day ! How Glory let them slake their thirst Where evil brain had done its worst,

And left a poisoned stream ! Still onward Glory's beckoning light Leads through the inky vault of night. Where the air bristles with affright And apprehensive dreams !

Has Glory other charms than these ?

Its radiance penetrates beneath The darkened fathoms of the seas

And there reveals the victor's wreath! Where craftily destroyers creep Among the dwellers of the deep,

In quest of human prey ! Sea-vampires, blood-suckers, or ghouls, With tentacles that bait for souls, Bidding the ocean as it rolls

Hide half their guilt away !

There is no infamy so great But Glory gilds the very deed,

Till our dulled senses estimate The values of a noxious weed,

As though 'twere Honour's stainless flow'r.

The amaranth of lawful pow'r

By Justice proudly worn !

Glory so flauntingly behaves

On land, in air, or on the waves,

That Britain's war-lords in their graves Must turn and writhe with scorn !

There's something more than Glory's dream That makes men choose a sordid death,

Victims of every evil scheme,

Dishonour tainting every breath !

Each building his own funeral pyre

In w'reathing flames of liquid fire Kindled by fiendish hands !

They feel no glory, where they lie

Half-sodden in some loathsome stye.

Some dug-out trap wherein to die, In weary, waiting bands !

There's something, — call it what you will, Revenge, — or outraged sense of right.

Or Nature's own instinct to kill Repulsive germ or parasite !

An impulse to bring down each threat

That dares to menace Britons yet. With arrogant conceit !

Each holds a brief for some dear life.

Defenceless mother, child, or wife.

And enters the ignoble strife. Us purpose to defeat !

With such a bold yet skulking foe There is no glory in the fight !

Truce-violaters cannot know

The line that severs Wrong from Right !

When lying murderers take the fieldj

Is there one Briton who would yield, Or would refuse to go ?

Although he sickens at the thought

Of battles that are foully fought,

Of honour that is set at nought, With mockery laid low !

No ! Not for Glory, nor for Fame !

As once 'twas said in Marlborough's day, But to avenge our own good name,

To stand by comrades, come what may! To stifle bullies in their shame. To make them taste their own low game,

Until their vauntings cease ; Nor ever call the war-dogs in, Till, with their quarry at Berlin, Their barks proclaim how Britons win An honourable peace !

|

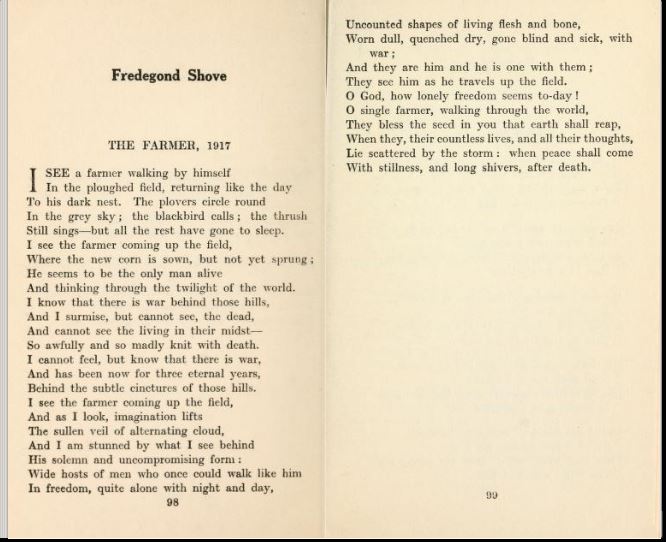

Inside page from

Anthology |

Sources: Find my Past, FreeBMD,

Catherine W. Reilly “English Poetry of the First World War: A Bibliography” (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1978) pp. 220 and 9;

https://archive.org/details/onehundredofbest02fors/page/108/mode/2up?view=theater

https://archive.org/stream/onehundredofbest02fors/onehundredofbest02fors_djvu.txt